In 2022, the website TasteAtlas published their annual ‘World’s Best Cuisine’ awards. The award involved ranking 95 world cuisines according to audience votes for ingredients, dishes and beverages, and its methodology and subjectivity were thus somewhat questionable. Perhaps unsurprisingly, Italian, Greek, Spanish, Japanese and Indian cuisines topped the rankings, and so the media were less interested in these predictable front-runners than in the cuisine with the dubious honour of coming bottom of the list: Norway.

Read moreOn the meals that never were

In the pilot episode of HBO’s hit series Six Feet Under, funeral director Nathaniel Fisher Sr. is hit by a bus while driving home on Christmas Eve. Receiving news of her husband’s untimely death, Ruth Fisher hurls first the phone, then the Christmas dinner she is in the midst of cooking, to the ground. A tray of roasted meat and vegetables clatters to the floor. Amidst staccato shrieks, she sweeps jars, pots, knives and plates from the worktop, then sits hunched against the oven, the dismantled debris of a pot roast around her feet. A ladle, slicked with grease, lies redundant on its side. ‘Your father is dead,’ she tells her son. ‘And my pot roast is ruined.’

Read moreOn missing breakfast in a pandemic

We’ve reached that awkward, liminal stage of the pandemic where, rather than simply wallowing in misery, weight gain and relentless tedium, it has apparently become acceptable to turn to another person (from two metres away, of course) and ask them: ‘Where is the first place you want to travel to, when this is all over?’ Now that there is the tiniest sliver of light at the end of the plague tunnel, thoughts inevitably turn to how we might embrace our new-found freedom. It has taken precisely two iterations of this question for me to become sick of it. My standard response, now, is simply to roll my eyes and say ‘Literally anywhere. I don’t care.’

Read moreTen things I've learned about food while living in Denmark

There are few pleasures simpler or greater than excellent bread and butter. Particularly when the butter is creamy and salted, and the bread is a freshly baked Danish bolle, or roll, available in numerous varieties: peppered with walnuts and dried fruit, sprinkled with poppy or pumpkin seeds, flecked with strands of carrot or beetroot… These always have the most luscious dense, slightly sour crumb, and are deliciously chewy and wholesome, particularly when slathered in the aforementioned butter. I should also mention that the Danes even have a special word, tandsmør, which literally means ‘tooth butter’ and describes a piece of bread so thickly spread with the good stuff that you leave toothmarks when you bite into it. This essentially describes the diet to which I have been rigorously adhering since I moved here.

Read moreCook for Syria

Sometimes people ask me why I love to travel. By ‘people’ I mean my mother, and by ‘sometimes’ I mean while I’m in the process of stuffing my 65 litre backpack into the freezer so all the Burmese bedbugs it contains can shuffle off this mortal coil amidst tubs of ice cream and frozen peas, or while I’m approaching my eleventh hour sleeping under a foil blanket on the floor of Stansted Airport waiting to be allowed to leave because a kind gentleman on my flight home mentioned that he’d put a bomb in the hold of the aircraft and apparently the police have to look into things like this, and it takes rather a lot of time. Time that trickles onwards in slow, sluggish gulps as you try and make the gratification from a crustless white bread sandwich endure for the entire night, and become far better acquainted with the minutiae of a Ryanair boarding gate than you ever thought possible, or desirable.

Read moreVilana cake

Vilana cake is an unusual sweet from the beautiful tiny volcanic island of La Gomera, in the Canary Islands, and is named after the ‘vilana’, or tin pot, in which it is traditionally baked. Thanks to its sub-tropical climate, La Gomera boasts fabulous produce – avocadoes, fresh fish, bananas, tomatoes – but the region is best known for its potato recipes, making the most of the island’s flavoursome root vegetables which arrived there shortly after the conquest of America. This simple, hearty cake incorporates mashed potato into its moist, buttery crumb, along with other key ingredients from the island: almonds, spice and dried fruit.

Read moreQuince tarte tatin

When my boyfriend and I arrived at our hotel in Crete this summer after a chilly 3.15am start, a long flight and a fraught attempt to navigate the Greek roads in an unfamiliar hire car, I was elated. My body hummed with intense joy. It wasn’t the sight of the empty blue pool, its rippled surface mirroring the radiant sun, nor the distant glow of the Mediterranean on the horizon. It wasn’t the sight of our pastel painted balcony, tangled with grape vines laden with translucent, plum-coloured fruit. It wasn’t even the knowledge that the bar would still serve us a huge Greek salad and a chunk of crusty bread despite it being far past lunchtime. No: my eyes swept breathlessly over the pool, the landscaped gardens and the cloudless sky and instead landed on the quince tree.

Read moreIndonesia: exploring through ingredients

My arrival in Indonesia was not under the most pleasant circumstances. My plane from Borneo was delayed for nine hours, leaving me stranded at (probably) Malaysia’s tiniest airport after all the shops shut with nothing to eat except for the complementary KFC offered by the AirAsia team when it became clear that, despite the assurances of the man in uniform waiting at the gate that the plane was ‘not delayed’ (he maintained this brave pretence for a good three hours after the time when the plane was supposed to have taken off), the plane was clearly not taking us anywhere anytime soon. I made friends with three very funny Malaysian boys who coaxed me intro trying some of their KFC and found my reluctance absolutely hilarious. I had to cave, after about seven hours. I was expecting this crossing over into the dark side to be sinfully delicious, to initiate me into the guilty pleasures of fast food that I have, for so long, abstemiously avoided. In actual fact, I ate the withered, flabby, tasteless chicken burger in dismay, finding it tasted of very little except the hard-to-place ubiquitous flavour of mass-produced spongy carbs and soggy batter.

Read moreTwenty-one things I learned in Thailand

Let's be realistic. No matter how long it sits on my 'to-do' list, I am never going to get round to delivering that lengthy, nuanced, insightful, evocatively-written, anecdote-peppered, florid prose masterpiece that is 'Elly's travels around Thailand' on the blog. I think I exhausted myself for life in that area when I wrote an almost book-length post on Vietnam and Cambodia a couple of years ago, and have never had the inclination to repeat the effort. I keep a hand-written travel journal and simply cannot find it in me to take the time to transcribe it for the benefits of the internet. But, since we're all obsessed with lists and bite-size chunks of information these days, I thought I would deliver a Buzzfeed-style recap of my trip that cuts out the boring parts and gets straight to the valuable, the memorable, the gastronomic...and the cat-related. Because I've heard the internet loves cats too.

P.S. Scroll down to the bottom for accommodation/restaurant recommendations.

Read moreBraised lamb shanks in Thai red sweet coconut curry

If it wasn’t the kilo of Parmesan cheese, it was probably the plastic bag full of dates, welded into a rugged block with crystalline syrup, from a market in Aleppo. Or perhaps it was the log of palm sugar wrapped in dried banana leaves, which I’d cradled while still warm after watching it made before my eyes in a Javanese village. Maybe the Balinese coconut syrup, darker than maple, its bottle festooned with palm trees and bearing a curious resemblance to tanning oil. If not that, it was surely the bundle of white asparagus, albino stalks tied together like a quiver of arrows, brought home from a market in the tiny town of Chablis.

Read morePostcards from Costa Rica and Nicaragua

I haven't updated this blog in a while; summer is always a busy time and although a lot of luscious cooking does get done, it somehow rarely makes it onto the internet except in the form of quick Facebook photos that either bear one of two captions: OMGYUM, or 'Yeah, I know right.' So I thought I'd take a moment to share some of my holiday photos from my trip to Costa Rica and Nicaragua in April. There aren't many of food, because a) they are all camera phone photos and so not aesthetically beautiful and b) I basically ate the same thing every day: rice and beans, plantain, and some form of protein. Which was nice but resulted in me going out for a pizza one night, something I vowed never to do while abroad anywhere other than Italy. It was an excellent trip involving beautiful jungle, zip-lining oh so high above said jungle while screaming at the top of my lungs, lots of wild swimming, papaya, horse riding, mojitos on tropical islands, wildlife, a couple of earthquakes, some turtles, boat trips, and unfortunately a very nasty incident involving 387 bedbug bites and a traumatic missed flight home...but let's forget that part and focus on the nice. See below.

Read moreAmok trey (Cambodian fish curry steamed in banana leaves)

Before I even go into the wild and wonderful merits of this beautiful dish, let’s just revel for a second in the fact that it’s called ‘amok’. Apparently this is simply a Cambodian term for cooking a curry in banana leaves, but I don’t think we use the word ‘amok’ enough in English and so let’s take a moment and think about how we can incorporate it more into our lives.

Good. Now you’ve done that, let me tell you about the beautiful amok.

Read moreFive things I love this week #9

1. Central American food.

I spent a couple of weeks in Costa Rica and Nicaragua this April, and although the prospect of rice and beans for every meal did start to get a little tedious (never before have I found myself going out for a pizza while abroad somewhere that isn't Italy...oh the shame), I am a fan of this simple yet hearty, wholesome, bolstering combination of ingredients. Rice and beans (all the better if fried with a little spice), fried plantain (sweeter and more caramelised in Costa Rica, like bananas, while crispier and more starchy in Nicaragua, like potato cakes), tortillas (soft and nutty, unlike the pallid flavourless things we buy in packets over here), and some form of protein: eggs for breakfast; fish, steak or chicken for lunch. You might also get some fresh cheese and/or avocado if you're lucky, and pico de gallo: a tangy relish of ripe tomatoes, onions and coriander. Perfect for breakfast and lunch, though I did crave a bit more variety for dinner. Luckily, there was ceviche to satisfy that requirement.

Read moreBali banana pancakes

The moments you remember most fondly from travelling are often not quite those you’d expect to recall or to take such a place in your heart. I have many wonderful memories from my recent trip to south east Asia: spotting an orang utan in the wild in the heart of the Borneo jungle; immersing myself in the sights, sounds and scents of one of Penang’s biggest hawker markets; snorkelling in turquoise waters off the coast of Sabah; walking through lush rice terraces in Java surrounded by papaya trees. And yet one of the moments I remember best, and that fills me most with a tranquil sense of happiness, is one that is comparatively trivial.

Read moreFire, ice and fermented shark: adventures in Iceland

“Oh right. Are you going for work then?”

“No, just for fun.”

“Oh, OK. So you have family or something out there?”

“No, nothing like that, I’m just going for a holiday.”

“Oh…so like, is it something to do with your PhD?”

My recent trip to Iceland seems to have perplexed more than a few people. I’ve been asked all of the above, plus a few more questions, as people attempt to determine the logical reason for my heading off to somewhere that’s a little bit off the mainstream tourist radar. Or perhaps they were just trying to grasp a rational motive for my jetting off to the frozen north just as York was beginning to heat up and become bathed in radiant sunshine.

I have to admit, I wondered the same thing myself as I stepped off the plane to gusts of freezing wind and stinging sleet, to skies greyer than a naval warship and a landscape bleaker than a morning without breakfast. On the bus ride to our hotel, I marvelled at the expanse of uniform moss, scrub and black soil, at the formidable-looking waves licking the rugged shore around us. I huddled into my goose-down jacket, which I had put away for the summer in York and had had to retrieve for the trip, adjusted my sheepskin earmuffs and braced myself for the cold days ahead.

Cold they were, and miserable at times, but this is a country that doesn’t need sunshine and balmy evenings to bring its magic to the fore. Yes, Iceland looks beautiful in the bright, clear morning sunshine (we were lucky enough to glimpse a few hours of it the morning we left), when the snow-covered mountains radiate a frosty grandeur and the sky and sea blend together in one uniform shade of blinding azure; but it is equally splendid, and somehow seems more comfortable, when its massive natural wonders and geographical marvels are silhouetted against a muted backdrop of greys and browns, hazes of drizzle, assaulting gusts of wind.

“In Iceland there’s no such thing as weather,” our taxi driver told us, “just examples.” This is a country hardened towards extremes of temperature and the capricious whims of mother nature, who, with a tendency towards hyperbole, has shaped its marvellous, and at times surreal, landscape.

We spent three days in Reykjavik, the adorably compact capital. An aerial view of the city presents you with something that more resembles a model town, perhaps built out of lego, than anything real. The houses are all painted in bright pastel shades, colours you might associate with a row of beach huts rather than dwellings built to withstand the cold and rain. Arriving in the city in the grey damp, they were a welcome burst of brightness.

Reykjavik, for me, was a curious mix of seaside down and ski resort. A few minutes takes you from the centre of town – straight streets, Parisian and Danish-style cafes, modern shops selling clothes, homeware, books, all of it exuding smart Scandinavian chic – to the harbour, where fishing boats sit idly in front of the glorified huts that house some of the city’s best restaurants, and the sweet scent of fresh seafood lingers in the air. You are cradled on two sides by mountains, lurking dappled grey across the distant sea. You stroll past ice cream cafes, shop windows filled with thick fur and wool garments, trendy bars and coffee shops, restaurants advertising their ocean-based fare. The centre of the city is tiny, easily explored in a few hours. Step into one of the uber-cool cafes and you could be in mainland Europe; step outside, and the freezing May weather reminds you that you are not.

“We’re not cool enough to be here,” was a niggling feeling frequently voiced over our three-night trip. It’s hard to be any more eloquent about it: Reykjavik is just cool. Every café or bar we visited exuded the same kind of aura: vintage, quirky, eccentric. They were often decorated with an assortment of kitsch or vintage so random it was hard to believe the place hadn’t just accumulated its décor over centuries of use. One café we visited twice was decked out like a Russian grandmother’s living room, all yellow-green chintz armchairs, old-fashioned floral still lifes on the wall and ornate gold frames. Another was brimming with retro toys – dolls, figurines, clocks, pages from books – voluminous spider plants and tables pasted with quirky adverts from old newspapers. We sat there and consumed two absolutely gigantic wedges of cake – a chocolate cake with chocolate buttercream icing, and a ‘New York cheesecake’ so claggy and sweet I almost needed a spade to scrape it off the roof of my mouth afterwards. One night we ate dinner at an achingly trendy youth hostel, housed in an old biscuit factory. Empty bird cages dangled from the dilapidated ceiling, one metallic wall was devoted to the arranging of magnetic letters by guests into rude words, a corner was given over to an enormous bookcase, and old-fashioned maps of the country were fixed, resplendent in vintage frames, to the wall. Although we did have the misfortune to spot a Subway, this is a city that has yet to fall prey to the plague that is the chain store: it’s all about those quirky little independent places, the kind you always dream of finding on holiday. They’re not a myth perpetuated by travel guides – they’re just all in Iceland.

Our exploration of Reykjavik began with a coffee in the aforementioned Russian grandmother’s café. Icelandic coffee is excellent. It reminds me of Italian coffee: strong, not very milky, cappuccinos served in small cups, not the ridiculous vats you get over here. They are predominantly coffee, rather than froth – probably what you’d call a small latte over here, in terms of lack of frothiness. I don’t drink coffee very much, but found myself craving at least one a day in Iceland. Partly because I was utterly exhausted from our exploring activities, but also because it tasted so damn good. The best came from what I think is a local chain of coffee shops, ‘Te & Kaffi’, which has several branches in the city. They also sell an adorable range of brightly coloured teapots, and some exciting-sounding bags of Chinese and Japanese teas, as well as some Icelandic herbal tea that claimed to be useful for treating a variety of ailments.

Pleasantly surprised by the coffee, we sought dinner at a restaurant I’d read good things about on the internet, Tapashusid (translation: Tapas house). When I tell you that this is a sort of Spanish/Icelandic fusion restaurant, I expect your scepticism. I was somewhat confused too, and a little apprehensive. Even more so when I ordered the six-course ‘Taste of Iceland’ menu for nearly £40 – disappointment is so much more bitter when you’ve paid forty pounds for it. It was a risk.

Instead, I spent around two hours devouring what was probably one of the best meals of my life. This place utterly astounded me. Inside it was informal-looking, again blessed with the vintage Midas touch that seems to have left no corner of Reykjavik unaffected – we sat in a little corner near a wall plastered with retro record covers. Blackboards over the bar proclaimed the specials, as well as a hilarious guide as to how the steaks are cooked (“Blue: still mooing”; “Well done: ORDER CHICKEN”). We were served by a series of effervescent and charming waiters, who occasionally paused to join in with the resident female flamenco dancer. All this, you would think, would probably not be the setting for incredible food. A quick glance at the menu, though – bacon wrapped monkfish with bacon-wrapped dates; minke whale steak with teriyaki sauce, smoked apple, apple puree and mushrooms; smoky mushroom tortilla; salt cod, langoustine, bacon and egg foam – did tell me that I was unlikely to be receiving a bowl of sub-standard paella and a few calamari rings.

The food here was heart-stoppingly beautiful. Probably some of the prettiest food I’ve been served since my last trip to the Michelin-starred Yorke Arms. My first dish was a small plate of rare guillemot breast, apple puree, smoked apple pieces, mushrooms and a red wine jus. I’d obviously never tried guillemot before, but it was gorgeous – like very dark, very gamey pigeon, but beautifully tender. Game and apple is a new combination to me, but it was stupidly good, the whole thing held together by an underlying smokeyness; I’m not sure whether it came from the meat, the apple or the jus, but it was so good.

Next, slow-cooked Arctic char, which looks and tastes rather like trout. This was accompanied by pickles, dill, a very creamy, Hollandaise-like sauce, and a little green savoury meringue. I knew then that the rest of this food was going to be good. There’s something about a savoury meringue sitting on top of your fish course that kind of implies subsequent sophistication. This was a lovely plateful; you can’t really go wrong with oily fish and dill.

Next up, a wooden board sporting food that was a complete work of art. There were two dishes perched atop this: first, wafer-thin slices of pale pink lamb carpaccio, a little spoonful of lamb tartare, cubes of red and gold beetroot, a thin shard of crispbread, and a golden ribbon of parsnip puree. I’ve never tried raw lamb before, but this was lovely – fatty enough to give it a lovely silky mouthfeel, but still possessing that sweet lamb flavour. The parsnip (I normally hate them, but this was quite tasty) and beetroot helped to cut the richness of the meat.

On the other side of the board, a dark and interesting assortment of cured minke whale, blueberry coulis, halved bulbous blueberries, mustard, a red wine jus and a drizzle of teriyaki sauce.

Now, I’m just going to take a step back for a second, because I can tell you that without a doubt there is going to be some holier-than-thou person, somewhere, who will read that I ate whale and decide to lecture me on the grotesque ethical implications of my gastronomic choices. So I’ll pre-empt you with some honesty: I admit that I had no idea about the controversy surrounding whale-fishing in Iceland. This is unusual for me, as I’m generally pretty clued-up on unethical food practices the world over – shark fin soup in China/Japan, foie gras in France (I refuse to touch the stuff; I think it’s appalling, sick, and it doesn’t even taste that nice), weasel coffee in south-east Asia; snake-heart vodka in Vietnam; battery farming (particularly pork, which many people seem to forget about) in the UK and Europe. For some reason, the whaling issue had slipped under my ethical radar, and I tucked in without really understanding the implications. Having read a bit more since I returned home, I’m actually not entirely sure where I stand on the whaling debate. However, the single whale dish that I ate in my trip to Iceland, which will probably comprise the entirety of the whale I eat in my entire life, is probably not going to tip the balance either way. Yes, I feel a bit uncomfortable about it, but I’m going to make no apologies for my one-off consumption of this controversial product.

And also, unfortunately, I cannot lie. It was bloody delicious. My minke whale came cured, meaning it had a firm texture and deeply gamey flavour. We also ordered, though, a dish of minke whale steak, served very rare with a similar flavour combination to my cured dish – apple puree, teriyaki sauce, red wine jus. This was a total revelation, both the meat and the flavour combination. It was like the tenderest, most juicy, melting fillet steak you’ll ever eat. Combining teriyaki, red wine, mushrooms, apple and game is something I’d never considered before, but something I now cannot wait to try. Obviously it won’t be with whale when I try it –I’m thinking more along the lines of venison, grouse or pigeon, and whale is illegal in the UK – but I can’t wait. It’s one of those combinations you can’t imagine until you taste it, and it was ridiculously good. Just take my word for it, and then hop over to Iceland so you can try the real deal.

There was a small wait for the main courses – yes, I know, those were only the starters – so I nibbled on some of the restaurant’s excellent foccacia, which they serve with olive oil to dip, and a little bowl of crushed salted spiced peanuts. Another flavour revelation – dipping oiled foccacia into crushed peanuts is DELICIOUS. Something I must try soon in my own kitchen. I’m glad I didn’t eat too much of this, though, because my main courses – all two of them – arrived, and they were pretty generous.

First, lamb rib-eye (a cut I’ve never heard of in relation to lamb, and which I suspect goes under another name here), which was the best lamb I’ve ever had. It was juicy and pink in the centre, smoky on the outside from the grill, succulent and sweet and fabulous. Lamb is a big thing in Iceland – much more so than beef. This came with ‘cauliflower couscous’, which I recently saw on MasterChef so was excited to try, a mustard sauce, a dark jus, and grilled oyster mushrooms. It was a carnivore’s delight, everything you want a plate of steak to be – juicy, salty, rich, meaty, robustly flavoured.

The other dish was equally substantial and robust – a mini decorative saucepan filled with ridiculously gorgeous chunks of salt cod – firmer, sweeter and saltier than normal cod – juicy langoustines, crispy bacon, and topped with an ‘egg foam’ which was basically a gooey, rich, thick hollandaise. This was finished with crunchy breadcrumbs for texture, and was the kind of thing I would eat for breakfast every day if I didn’t mind being obese. I loved the way the restaurant had struck a balance between delicately presented, beautiful food, and the kind of mouthwatering moreish flavours that you actually want to stuff yourself with. The other dishes we tried – the monkfish with dates and bacon, deep-fried langoustines, smoky mushroom fajita – were also in this vein; surprising flavour combinations that made you wonder why you don’t eat them every day, because they are so damn good.

Also fabulous were a dish of bacon-wrapped monkfish, roasted peppers, and bacon-wrapped dates, a plate of deep-fried langoustines, crispy and sweet and delectable, and a smoky mushroom fajita - deeply flavoured, intense mushrooms on a tortilla with tangy cheese.

Dessert was a struggle. You know how sometimes you worry about tasting menus, thinking they’ll present you with a thimbleful of each dish and leave you desperate for a piece of toast when you get home? This left me desperate for a Roman-style feather when I got home (note: this is a joke and I do not, in fact, support bulimia as an easy way to alleviate that feeling of self-disgust that accompanies a session of wild, intense, unmediated gorging). However, my dessert was sensibly light and pretty, and didn’t make me want to cry and run away in grotesque repletion when it arrived.

It consisted of a thin slab of moist carrot cake, a carrot sorbet (surprisingly good – I think it had a hefty dose of orange in there, because it was sweet and fruity and tasted very little of carrot), and a parfait of ‘skyr’. Skyr is an Icelandic cheese, made in a similar way to Middle Eastern labneh – by straining yoghurt until firm and tangy. Its pairing alongside the carrot cake made sense – it was basically a fancy version of carrot cake with cream cheese frosting. The dessert was sprinkled with tiny, plump, marigold orange buckthorn berries, something I’ve always wanted to try since they were used on Great British Menu a few years ago. They are deeply sour, but also quite fruity, a very pleasant addition to the mellow cake/cheese combination. We also had an ‘Oreo pudding’, which was a chocolate mousse (pronounced ‘chocolate mouse’ by our waiter, which made us smile), blueberry compote, crunchy oreo crumbs, and a ball of ice cream. It was the total antithesis of my elegant dessert, trashy and obvious and in-your-face, but in a totally delicious way.

And that was my introduction to Icelandic cuisine. I have a sneaking suspicion that Icelanders do not eat like this on a daily basis, but it set the tone for a trip of excellent restaurant meals. This, at Tapashusid, was by far the best. It wasn’t cheap, but it was worth every penny, both for the temporary gratification it afforded me and also for the ideas it has given me for use in my own kitchen.

Speaking of money – Iceland is expensive. Probably not much more so than London, but it is hard to spend under about £50 a day, and if you want to do the kind of things you should do when visiting this unique country – ride horses, visit the Blue Lagoon, go on boat trips, see the geographical wonders – you will have to spend even more. It is possible to eat cheaply if you’re not bothered about sampling some of the gastronomic delights of Reykjavik – there are some fast food places and cafes selling sandwiches – but the good food comes at a price. Luckily, you don’t have to pay that much to get something delicious, as some of my other restaurant visits will show.

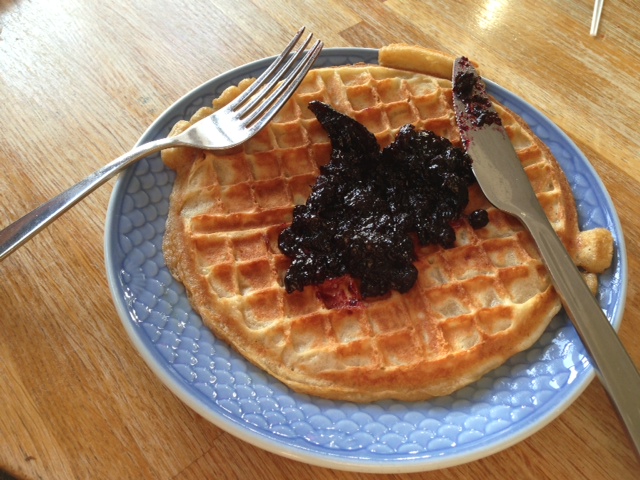

Barely hungry from the gluttony of the night before, I woke the next morning and forced myself to partake in our hotel breakfast – what a hardship. We stayed at the Leifur Eriksson hotel, in what I like to call the ‘penthouse suite’ but what was actually an absolutely tiny attic room on the top floor barely large enough for two people to stand up in without concussing themselves. It was cosy, that’s for sure. That aside, the hotel was perfectly pleasant, and breakfast was a bit of a highlight. In the corner of the breakfast room stood an arresting contraption: a waffle maker, with two hot plates, completely black and encrusted from years of use, smoking and perfuming the entire hotel with the sweet candyfloss scent of freshly made waffles. Next to it sat a big bowl of pale, thick batter, and a ladle.

I am baffled as to why the hotel hadn’t put up some instructions next to the waffle maker. In the three mornings I was there, at least two people had what can only be described as a complete waffle fail. There’s a knack to making waffles, you see – firstly, spray the plate with non-stick oil spray. Secondly, put enough batter – more than you would think – in, otherwise it won’t form a proper waffle and will just stick to each side. Thirdly and crucially, be patient. If you lift up the lid too soon, the waffle will pull apart and you’ll just have batter stuck to each side, impossible to remove (the staff were not happy – there was an audible tut as they set to work with a knife attempting to deal with the consequences of one guest’s waffle ineptitude). Fortunately, I managed to perfect this complex and elusive art very quickly, meaning we had perfect waffles for breakfast each morning. They were fabulous – thick, doughy, crispy on the outside, and subtly sweet and buttery. On top, generous dollops of blueberry jam – actually, I think it was bilberry, or wild blueberry – which was delicious but had the unfortunate side effect of giving me a bright blue tongue that no amount of toothpaste/toothbrushing could shift.

Our first full day took us out of the city into the forbidding landscape. We began by riding Icelandic horses through the lava fields, in all their bleak, rugged glory. The terrain is unchanging around here – earthy green moss and scrub, punctuated by dark black roads of cooled lava, the imposing mountains ever-present in the background. It wasn’t the most scenic, particularly given the steely skies, but this was more than compensated for by the fun I had riding my horse. His name in Icelandic translated as ‘little man’, and he was indeed tiny – like a slightly overgrown Shetland pony, a beautiful tan colour with the most gorgeous thick, sandy mane. I feel we bonded early on, as I led him by the bridle out of the stable – he kept nuzzling me with vigour. Later I discovered that he was just trying to use me as a scratching post. Oh well.

Most of the people in our large group had never ridden before, so we walked at a steady pace in single file through the lava fields. I soon felt slightly frustrated by this, as I could tell my little horse was eager to go a bit faster (or maybe it was just that his legs were about half as long as the other horses’, so he had to trot to keep up with their walk), so I joined the ‘fast group’ for experienced riders. I’m not sure I’d consider myself an ‘experienced rider’ – that implies a degree of confidence that I do not have, my recent experiences with horses involving falling off or them bolting - but I figured I’d take the chance, and am so glad I did. I had a fantastic time, riding through the countryside, my little horse keen and fast but also very well-behaved.

My guide told me all about Icelandic horses, which was fascinating. There is a complete import ban on Icelandic horses to preserve the purity of the breed. When the horses go abroad to compete in international competitions, so strict are the rules that they can never return to Iceland, and must be sold in the country of the competition. This isn’t so bad if they’ve won, my guide explained, as they’ll fetch a good price – but the worst situation is when the rider has an excellent horse, but for some reason he doesn’t perform so well in competition, meaning the rider has lost both his horse and won’t even receive adequate financial compensation for his loss. Foreigners are also not allowed to bring used horse equipment into Iceland – hats, bridles, et cetera – or at least not without it being heavily sterilised first. They don’t vaccinate their horses, she explained, so their immune systems are quite susceptible to diseases that can be carried on used equipment.

The riding style is very different, too, to what I am used to. For instance, riders don’t rise during the trot – they stay sitting on the horse. This makes for an extremely bouncy but definitely less exhausting ride; it was slightly alarming at first, as I was convinced I was going to fall off, but I soon got used to relaxing and moving with the horse. The Icelandic horse also has a different set of gaits: tölt is faster than a walk but slower than a canter, and it is also very smooth for the rider. My guide was telling me that sometimes competitions are held where the rider holds a pint of beer for the duration of the ride, the aim being not to spill any, and then they must drink the remainder upon returning from the ride. There is also ‘flying gait’, which is faster than a gallop and so-called because in between strides the horse appears to be flying through the air; many horses aren’t trained to do this, though, because it’s exhausting for the horse and rider. I was certainly quite tired after my brisk and bouncy outing on my beautiful Icelandic horse, which was lucky because we were going to spend the afternoon steaming luxuriantly in a hot outdoor bath.

The Blue Lagoon is one of Iceland’s top tourist attractions. It’s easy to see why – with weather so changeable and a landscape so bleak, there is unmatchable relief to be had from sinking slowly into mineral-rich waters the temperature of a very hot bath, the result of geothermal activity, while the brisk Icelandic air whips your face. I say ‘sinking slowly’, but this is really just a romanticised notion. Because, in fact, you’ll dive frantically and in a clumsy, ungainly fashion into those waters: not only do you have to make your way from the changing rooms to the outdoor lagoon clad in nothing but your swimsuit, but they make you shower before you do it, meaning even the slightest tremor of Icelandic wind feels like someone has pressed an ice pack to your skin. Once in the lagoon, however, sweet relief is to be found. It really is hot, not the shiver-inducing lukewarm temperature of most UK outdoor swimming pools that claim to be heated. In fact, in some places the currents are almost scalding, and your otherwise relaxing dip in the lagoon is certainly likely to be punctuated by a few high-pitched shrieks every now and again, as one of these scorching currents wafts casually into an unsuspecting bather.

The water is milky, completely opaque and with a curious iridescence; it almost glows, particularly when the skies are so grey and flat. Thick steam rolls off the surface in waves. There is a smell of egg-like sulphur in the air (another thing about Iceland – the tap water smells of boiled eggs, making brushing your teeth an interesting sensory experience). Depending on which part of the lagoon you are in, you’ll either be standing on crunchy gravel-like sand, or sinking into thick mud that oozes creepily between your toes. It’s quite something, though, to sit there, face and neck exposed to the harshness of the elements (it started raining during our visit) while the rest of your body luxuriates in the delicious warmth. The high mineral content of the water is apparently very good for your skin, though leaves a horrible chalky residue that requires two showers to remove. As you sit and warmly repose, you’re surrounded by rocky outcrops that you can perch on. There is nothing else to see, for miles around – the lagoon lies in the middle of nowhere, a surprising beacon of blue among the dark rocky landscape. It’s hard to believe this is a totally natural phenomenon.

Horse riding and the lagoon left me absolutely starving. That night, we visited somewhere a little more budget-friendly for dinner, and weren’t disappointed. Icelandic Fish & Chips is a small café/restaurant near the harbour (choosing where to eat in Reykjavik is easy, because all the recommended eateries are approximately one hundred metres away from each other, so you can quite easily scout them all out in a ten minute session before making that all-important decision). You’d barely notice it if it weren’t for the sign above the wooden door that you have to open gingerly, peering around to see if the place is actually open – it’s hard to tell from the window. Inside is a very simple restaurant with a small bar and more blackboard notices on the walls. The premise behind this place is, as you might expect, fish and chips – but done well, and made a little unusual by their choice of accompaniments.

A lot of thought has gone into the food at this ‘organic bistro’, as they like to call it. The fish is coated with a batter made from spelt flour, because it crisps up better in the fryer and is better for you, being a more complex carbohydrate. They serve the fish with oven-roasted potato wedges, which are a little healthier than chips, and come in various options – plan, garlic, rosemary, for example. They fry their fish in rapeseed oil, high in omega 3. The fish is always fresh, the menu changing depending on what has been delivered that day. You are encouraged to choose a salad to accompany your fish, which range from simple greens to an elaborate combination of mango, red pepper, toasted coconut, spinach and olive oil. Finally, you can choose from a range of ‘skyronnes’: flavoured dips made from skyr, with flavours like truffle & tarragon, ginger & wasabi, lime & coriander. This is a far cry from the greasy, lard-scented chippies of the UK; not a wooden fork or piece of newspaper in sight.

We both had the fried Icelandic cod with plain potato wedges, the aforementioned mango salad, and a lime and coriander skyronne to accompany it. It was exactly what I needed after a hard day’s exertion (OK, sitting in the lagoon wasn’t really difficult, but it was certainly appetite-provoking): indulgent because of the superbly crispy fish batter and the sweet, succulent cod, but still nourishing and satisfying because of the zingy, flavoursome salad and well-seasoned potato wedges. It probably didn’t need the dip, but it was tasty all the same. I’d also been eyeing up a delicious-sounding combination of fried ling (a firm white fish), orange and black olive salad and rosemary potatoes; we didn’t have time to return, but I bet it would have been delicious. Our plates were about £14 each, which isn’t cheap but they were filling and very well done.

A quick aside: one of the things I really liked about Iceland was that every single café and restaurant had a table with jugs of water and glasses for you to help yourself – no need to ask for tap water and risk a sneer. Similarly, everywhere seemed to have free wifi (even the tourist buses), and public toilets are widespread. In these three respects, it is a world away from continental Europe.

Another aspect I enjoyed was the long daylight – the sun didn’t set until around 11pm when we were there; it’s even later in high summer. There is something quite disorientating and surreal about emerging from a long restaurant meal at 9.30pm to bright daylight, or settling down to sleep for the night while there is still light sky outside the window. Icelandic people must get so much done at this time of year. I did feel a bit bad that we didn’t do much to make the most of the longer light, but I was exhausted after all the food and activity.

Our second and last full day saw us taking in the Golden Circle, a 300km loop of some of Iceland’s best geographical attractions, by coach tour. We drove through the mountains, gloomy and imposing in the overcast light of day, through ‘no man’s land’, the area between the American and Eurasian tectonic plates, past dark green fields and black lava, past rocky hills and snowy mountains that are apparently the homes of elves. There were no animals in sight other than the Icelandic horses. Our guide told us that you can look at an Icelandic horse to tell the direction of the bad weather – they face away from the wind and rain. Given that Icelandic lamb is supposed to be a delicacy, I thought it strange that I didn’t see a single sheep on my trip.

Before we actually visited any of the geographical marvels, we stopped at a ‘greenhouse town’ on the way, so-called because farmers use the high geothermal activity in these areas to power greenhouses and supply Iceland with exotic fruit and vegetables that wouldn’t otherwise be producible. This particular greenhouse grew tomatoes. The owner explained that the water comes out of the ground at 95C in this area, the heat of which is channelled into the greenhouse system. The tomatoes are watered with the same water that people drink – because, he explained, a tomato is about 90% water, it makes sense to use good-quality water to grow the crop, as that quality will be reflected in the final product. The lights in the greenhouse are on 14-17 hours a day, and the plants grow 25cm each week – they have to be suspended from the ceiling on strings so they don’t droop with the weight of the fruit. The transition from a flowering plant to a red tomato takes about eight weeks. One aspect of the process I found fascinating was the pollination – bees are shipped in from Holland to perfom this careful task. Two boxes containing 60 female working bees arrive at the greenhouse each week.

The greenhouse had a little café, which was offering mugs of tomato soup. I mention this because of something I loved – each table had a huge basil plant on it, with a pair of scissors strapped to its pot. The idea being that you would get a mug of soup and snip your own basil to garnish it. It was the simplest idea but so lovely; I hope it catches on in cafes at home. Think of the possibilities – chopping your own coriander to adorn a curry; snipping your own parsley or dill to scatter over your seafood; tearing off delicate leaves of thyme to season your Sunday roast.

After this somewhat random first stop, we were taken to Gullfoss waterfall, first step on the Golden Circle itinerary. This absolutely gigantic waterfall formation appears startlingly smack bang in the middle of an otherwise fairly featureless landscape: green scrub, black soil, mountains in the distance. The sheer force of the water as it plummets over the various crests of the waterfall is astounding, as was the force of the freezing wind as we walked along paths hugging the edge of the cliff to get closer to this watery spectacle. I’ve seen waterfalls before, but none on this colossal scale. At one point a company tried to privatise the waterfall and use it for hydroelectric power, but the idea caused storms of protest and since then Gullfoss is protected for public enjoyment. Apparently there is a saying in Iceland: if someone suggests something completely inane or ridiculous, the common response is, ‘And then what? Sell Gullfoss?’

Next, we visited the Geysir hot spring area. With its gloomy, rugged, earthy landscape awash in white smoke emanating from the ground, this reminded me of the Dead Marshes from the Lord of the Rings. The air is thick with the smell of sulphur, while a walk through this geothermally active area sees you alternately exposed to the cold Icelandic air and bathed in hot steam droplets as the vapour pours off the ground into your face.

Along the way there are small pools, some of them mini geysers, bubbling rampantly and sending hot spray into the air. The main attraction, though, is Strokkur, the famous geyser, apparently active for over 10,000 years, that erupts every few minutes to raptures of delight from the crowds inevitably gathered around its circumference, cameras poised to capture the moment.

Every so often, the innocuous-looking, calm blue pool that is Strokkur suddenly vents a colossal bubble, followed by a gigantic blast of boiling water – at least twenty feet high – that is no less surprising for being expected. At one point some of the crowd had to run backwards as the hot water, carried by the wind, descended upon their heads. The force with which it erupts, and the height, is really quite remarkable, particularly as it returns so quickly to a lake of placid blue calm, only an occasional bubble signifying the colossal geothermal activity occurring within those depths. Apparently only 100m down into the geyser, the temperature is 200C. It’s definitely a ‘look but don’t touch’ kind of attraction.

We stopped for lunch and a break from the assaulting rain at the tourist café which, as might be expected, was hideously overpriced – I objected to paying £12 for soup and some bread, so had an egg sandwich. Oddly, the omnipresent smell of sulphur had actually given me serious cravings for eggs, rather than – as might be more expected – a complete aversion. A small highlight, though, was a piece of apple tart. This seemed to basically combine everyone’s dessert fantasies into one: a pastry case, filled with custard and cooked apples, topped with crumble and drizzled with caramel. It did have that slightly soggy mass-produced taste to it, like something from an Ikea café, but it was pleasantly sweet and tasty all the same – just what we needed after hiking up the hills around the Geysir area and getting absolutely covered in quicksand-like thick red mud.

Finally, we visited Thingvellir National Park, home to Iceland’s parliament from 930 to 1262, which incorporated the geography of the place into its proceedings: speeches were held around the Logberg (Law Rock), while transgressors were executed in the Drowning Pool, a small lake at the foot of the rocks. Here you can actually see the North American and Eurasian tectonic plates pulling apart, and witness the gulf between them. The area is rocky and hilly, with gorgeous views of Lake Thingvallavatn (formed by a retreating glacier) and the surrounding mountains; it was how I imagined the Norwegian Fjords would look.

On our way back, our guide told us something fascinating about the Icelandic language (words of which it is possible to recognise from my brief dalliance with Old English during my Masters). During the 18th century, a movement was started in the country to remove as many foreign words as possible from the language, and create a new vocabulary that would adapt the Icelandic language to new concepts, rather than imposing foreign words. For example, the computer: it was decided (for some reason) that a computer can see into the future, and that it works with numbers. Thus the Icelandic for computer is a portmanteau of tala (number) and völva (female prophetess): tölva. I’d heard something of this before, when someone once told me that the Icelandic for ‘coathanger’ literally translates as ‘wooden shoulders’. I love the idea that there is actually a committee dedicated to coining new words for modern concepts out of this ancient language.

Dinner that night needed to be substantial, given our day trekking around in the wind and rain. This was achieved in the best possible way by a trip to Sæmundur i Sparifötunum, the restaurant of Kex Hostel (the one discussed above, with the birdcages). Though the menu offered some tempting options – fried plaice with pickled lemons, burned butter and almonds; fried and glazed turkey with mushrooms and bacon; lamb meatballs – it had to be the burger, which promised local free-range beef, Icelandic cheese, caramelised onion mayonnaise, and potato wedges with cumin mayonnaise. It was probably the best burger I’ve ever eaten, everything you want a burger to be. The bun was robust enough to hold the burger without tearing, nicely toasted on top for a little texture. The meat was rich and deeply flavoured, the cheese tangy and creamy, the mayonnaise holding everything together. The potato wedges were just insane. They were the crispiest things I think I’ve ever eaten, seasoned beautifully, and the cumin mayonnaise was just an inspired idea. This was proper big, hearty comfort food, but taken to the pinnacle of perfection – much like the fish and chips of the night before. Not bad value at £14, either – probably what you’d pay in a London gastropub. Plus you could help yourself to very nice bread and butter, so there was no danger of us leaving hungry.

Afterwards (still daylight!), we went to a little ice cream café, Eldur and Is, where I had a crêpe with bananas and pecan caramel ice cream. The menu pointed out that the crêpes were made with spelt flour. This seems to be a bit of a thing in Iceland – several menus had mentioned spelt chocolate cake, while Icelandic Fish and Chips used spelt in their batter. I don’t know if maybe the flour is cheaper there than ordinary white flour, or they’re just more health conscious. Either way, the crêpe was tasty.

While I was eating it, I watched the man behind the counter dip a huge Mr Whippy-style ice cream on a cone – the ice cream must have been standing at least six inches high – upside down into a vat of molten chocolate sauce. How the structural integrity of this calorific creation was maintained I do not know; it was quite remarkable to watch. The dessert of choice in Iceland, crêpes and ice cream aside, seems to be a mousse of skyr served with various fruit compotes, chocolate, or nuts. I didn’t try this, though, as I’m not a big fan of creamy desserts – I like them to have a little more texture (read: stodge).

On our final morning, we got up early to head out on a boat and watch puffins. This was immensely exciting, as there are few things funnier to observe than a puffin. They look so out of proportion, with their huge coloured beaks and their little wings, flapping desperately in the air as if struggling to stay airborne. We visited an island home to thousands of them; there are around 10 million in Iceland. Our guide told us a little about these birds: their black backs and white bellies provide camouflage while underwater – if something is above the puffin looking down, it sees only the dark of the water; if below and looking up, it sees the white of the sun shining down on the water. This is true for a lot of ocean animals – fish and whales included. I’d never thought about this before – why fish have light bellies and dark backs – and found it fascinating. Puffins can dive to 40 metres underwater, and they mate for life, somehow carving out little holes in the side of islands in which to rear their young – they have only one baby at a time. The babies are called – wait for it – pufflings, which is possibly the most adorable thing I have ever heard. Sadly we were too early in the year to see any pufflings, but it was a very enjoyable morning spent upon the boat watching these funny creatures through binoculars.

Incidentally, the weather finally brightened up for our final few hours in the country. This was how I’d imagined Iceland to look – completely clear frosty blue sky, bright ocean, majestic snowy mountains in the background. It was beautiful, and a completely different experience strolling the town with the warmth of the sun on our faces.

My final meal is worth mentioning, largely because it presented me with the opportunity to try fermented shark. Innocuous enough, the shark was served in small cubes – resembling ceviche – in a little ramekin. It was pale, white and firm. The first few seconds were fairly pleasant. There was a light, sweet taste; a firm, meaty texture, reminiscent of good sashimi. I was rather enjoying it, until a rancid wave of searing ammonia hit my palate, stinging the roof of my mouth and engulfing my sinuses with its acrid tang.

Fermented shark is definitely not the ideal introduction to Icelandic cuisine. When fresh, the Greenland shark is actually poisonous due to its high urea content. After being buried in gravel, pressed with heavy rocks for six to twelve weeks and then cured for several months, however, it is miraculously transformed into a local delicacy, something that can be eaten. Whether it should be, of course, is another matter. Newcomers to this unusual foodstuff are advised to hold their nose, as the shark packs a hefty aromatic punch of ammonia, exuding an aroma that I can only describe as a cross between toilet cleaner and strong cheese. I’m normally pretty adventurous with food, but fermented shark can go on my ‘never eating again’ list, alongside andouillette, a French sausage made from the colon of a pig and tasting exactly like the colon of a pig.

This gastronomic adventure took place at Café Loki, a lovely little venue about twenty metres away from our hotel and right in front of Hallgrimskirkja church, the largest church in Iceland and an imposing, modernist building that reminded me a little of Minas Tirith (more Lord of the Rings similarities here…I wonder if Tolkein ever visited Iceland).

The café was light and airy, and offered an array of Icelandic dishes as well as more standard fare, like bagels and cake. I went for a plate of Icelandic specialities, which included the aforementioned shark. Other than that, though, it was very tasty indeed – I had rye bread topped with smoked trout and cottage cheese, rye bread topped with a delicious mixture of herring, potato, cheese, chives and onion (which looked like scrambled egg but tasted, deliciously, like a fish pie), and – my favourite – rye flatbread topped with butter and smoked lamb. This appeared in various places on my travels, and is really satisfying – the bread is dense and squidgy with a nutty flavour, while the butter is creamy and the lamb subtly sweet and smoky. I also tried dried fish, which you’re supposed to spread with butter and eat, but this was a bit odd – the fish was indeed very dry, so quite difficult to eat and a bit of a strange experience. At least it wasn’t fermented, though.

And that was it – a whirlwind tour around a remarkable country, with plenty of opportunities for eating along the way; a journey home fuelled by fermented shark. There is a lot I wish we’d had time to do – whale watching, snorkelling (the water is the clearest in the world, you can see for up to 100 metres), more horse riding, trekking – but I think I got a fairly good feeling for the place. It was so different to anywhere I’d visited before – normally my holiday destinations are substantially hotter and more tropical than the UK – and presented me with things I’d never seen before.

Perhaps it was rather a strange holiday destination, but Iceland is certainly somewhere you should visit at some point in your life, if only for the way it presents you with the unexpected and the marvellous every day. It’s geography taken to the extreme, and experiencing the culture that has been shaped from that rugged landscape and hostile climate is certainly an adventure. More than all that, though, the food is excellent – exciting, unusual, revelatory, and often beautiful.

Fish, fruit and pho: food travels in Vietnam and Cambodia

It's five months since I returned from my trip to Vietnam and Cambodia, so perhaps it seems odd to be posting this now. Recently I wasn't sure that I ever would post it. I returned to England - having not slept in 36 hours and carrying four gigantic suitcases containing everything from kimonos to chopsticks, from tea sets to boxes made out of cinnamon wood - armed with a notebook full of food-related memories and a host of noodle-related photos on my camera, determined to write an epic entry all about the food on my travels.

Then, as the days passed, I just couldn't bring myself to sit down and write it. This in part was due to laziness - one eats rather a lot in thirty-one days, and since pretty much everything I ate was worth documenting, the mammoth task of writing it all up was just too daunting. There was also a part of me that felt the memories would be ruined by putting them on here, by turning reminiscing into something too much like work.

Recently, though, I've realised how much I value posts about food I've eaten in other countries, like those on Prague, Italy, and the Middle East. Reading them over months or even years after the trips is a little like being there again. I remember dishes I'd completely forgotten, that I loved at the time, and I'm reminded to recreate them. Inextricably linked with those recollections of food are those involving places, sounds, smells, sights - all the little details you drink in while travelling but forget once the greyness of England has reclaimed your soul.

Although I may have lost something by not writing up my memories of Vietnam and Cambodia as soon as I returned, I don't feel it's too late. I still think about that trip every day, without fail, and I still feel almost crippling pangs of nostalgia and pining at certain moments - a song comes on my playlist from an album that I listened to almost continuously while out there (Ben Howard, Every Kingdom, should you be wondering); I find myself chopping up jagged shards of palm sugar that I bought in Cambodia; I go to sleep under a beautiful silken elephant bedspread, a souvenir from Siam Reap; I drink a cup of lime leaf or lotus leaf tea; I eat dinner with the chopsticks I purchased in Saigon. All these things serve to jog the memory in a powerfully bittersweet way. If something can conjure up that much emotion so long after the event itself, I feel it is worth writing about. I also hope anyone who reads it will enjoy it too - I promise not to be too self-indulgent - and maybe find inspiration to hopefully travel there themselves one day or, at the very least, cook up a new and exciting noodle dish.

I thought about the best way to arrange this post, since there is just so much to say, and I decided that the best way would be to work chronologically and geographically. I started my trip in Hanoi, so will begin there.

Well, technically, I began my trip in Saigon. After a gruelling 24-hour journey, involving two flights and a seven-hour stopover in Dubai, we arrived in Saigon, or Ho Chi Minh City (I'm still not sure which name to call this city by, and find myself alternating as the whim takes me). My initial impressions were of the humidity and the chaos of the place; the taxi ride to the hotel was a constant succession of pulsating neon lights and car/motorbike horns. Said neon lights were an interesting medley of advertisements for 'Massage' and 'Karaoke' (which often implies a brothel), and the giant outlines of pagodas, often affixed to restaurant facades. It reminded me of New York, only rather more ramshackle and mad. After checking into our hotel, we wandered the vicinity for a while, but in my exhausted state I found all the sights, smells and lights somewhat overwhelming. I saw delicious food being piled into bowls on every street, but - not speaking any Vietnamese and having no prior experience of east Asian culture - had no idea how to approach any of it and found the whole thing a little too intimidating. I went to bed, figuring I'd have more energy in the morning.

Wandering Saigon for a morning, my main highlight was finding the most wonderful smoothie stall, right near our hotel. These smoothies are so far from the stuff we get in the UK in (hugely expensive) bottles that you'd barely recognise them. A poster displayed a list of every fruit imaginable, including some I'd never tried or even heard of, and you could ask for your own combination to be blended up in front of you. I played safe with mango, pineapple and passionfruit. It came in a glass taller than my own face, garnished with slices of fresh pineapple and passionfruit seeds. After the tiring journey of the day(s) before, and coupled with the intense humidity, it was like drinking nectar.

This had a profound and lasting effect on my entire trip; wherever we went next, my first priority was to find a smoothie stall. I drank at least one every single day, my favourite being a 'mango shake', which I think tastes so good in Vietnam because they add a lot of sweet condensed milk to it. I never watched as these smoothies were made, preferring to be blissfully ignorant of how fattening my beverage of choice truly was. Besides, in the exhausting heat, I figure I'd earned it.

The most incredible part was that these smoothies never cost more than the equivalent of 80p. I couldn't believe it. In England, you'd pay at least £5 for the privilege of having fresh fruit blended with ice before your eyes and put in a plastic cup. In Vietnam, where the tropical fruit is so much fresher and sweeter, it costs a fraction of the price. As an ardent lover of fruit, I could barely believe my luck. Coming a close second to a mango shake was a papaya shake, which I drank every day in Cambodia. Papaya is one of my favourite fruits, and when combined with condensed milk or - as I had in Hanoi - coconut cream, makes for basically a dessert in a cup. I never found a smoothie stall as good as that one in Saigon, though, which perhaps explains why it was always so busy. Moments spent perched in its dingy alleyway on little plastic stools, sipping sweet, cold fruit as the sweat ran down the back of my neck, were moments to be savoured.

Visiting Ben Thanh market in Saigon also prepared me for the wonder that is the Asian market. I was assaulted by the scent of dried shrimp and fish, sizzling meat on a grill, wafts of aromatic noodle broth emerging from giant cooking vats, the omnipresent aroma of the infamous durian fruit (more on that later, it deserves a whole paragraph!) and the heady scent of freshly ground coffee.

The market sold all sorts of clothes and souvenirs too, but this is a food blog, so I'll keep it gastronomic.

There were piles of translucent, vivid orange dried shrimp, in all grades and sizes; huge stiff fillets of dried fish hanging from rails; piles of vivid guava, dragonfruit, rambutans, mangoes, custard apples, bananas, pineapple; huge jars of tea leaves and coffee beans; numerous jars of different types of chilli sauce, fish sauce, soy sauce. In the middle of it all there were stalls selling food to eat there and then. Overwhelmed by it all, we followed our eyes and noses to a busy stall producing delicious-looking food. I ordered fresh spring rolls and bun cha, two classic Vietnamese dishes I was keen to try.

Once you've had a fresh Vietnamese spring roll - slightly squidgy rice paper wrapper, crunchy vivid green herbs, soft tangle of rice noodles, tender and flavoursome prawn, pork or crab, sweet-sour dipping sauce - you'll never want to touch those greasy Chinese restaurant versions again. They're a textural delight, filling and delicious. Bun cha - cold rice noodles with grilled pork, herbs, and a sweet-sour dipping sauce - is in the same vein. Everything is so fresh, crunchy and vibrant, healthy but indulgent at the same time.

This was the moment I, to be nauseatingly clichéd, fell in love with Vietnamese food. Before my trip, I'd been a bit 'meh' about Asian food. I would eat it, and enjoy it, but my idea of going out for dinner as a treat never stretched to Asian food. I considered it fuel, rather than something to be seen as special. Now, given a choice of restaurants, I will always go for Asian food. I have been completely won over by its freshness, its healthiness, its miraculous understanding of texture and contrast, all thanks to Vietnam.

We had an awful flight to Hanoi, involving huge amounts of turbulence. As a nervous flyer, I found this rather traumatic. I found it much more traumatic later, however, when we arrived in the city and saw that the storm into which we had flown had actually uprooted trees from the pavement and smashed them into houses. A spine-chilling moment if ever there was one.

Hanoi is not what you would call pretty, but I loved it. It has an old-world charm about it, with its narrow streets, even narrower buildings, bustle of shops and markets, and beautiful lake. It is full of life in a very different way to the much more modern and Westernised Saigon. It was also my first experience of tropical weather, and the first and last outing of my lovely new leather sandals on my trip. After a couple of hours trudging around deep grey puddles, they were swiftly relegated to the bottom of my backpack and replaced with a nasty cheap pair of foam velcro sandals. So constant and torrential was the rain that a maroon plastic poncho became my best friend. I like to think it helped me to blend in with the locals. Until they saw my face or the colour of my hair, that is.

Also, I know this is a food blog rather than a travel blog, but if you're going to Hanoi, I'd highly recommend staying at Hanoi Guesthouse. It's right in the centre of the city, it's a very attractive little hotel (they put rose petals on our beds for when we arrived - shame we weren't actually a couple), and the staff are beyond friendly; they will go out of their way to make sure everything is perfect for you, bringing you cold drinks every time you come back after a hot day sightseeing, arranging Halong Bay tours, booking train tickets, etc. Also, the pineapple pancakes at breakfast are delicious.

My first meal in Hanoi was at a restaurant across the street from our hotel. I had cha ca thang long, a dish of white fish cooked in a turmeric-rich broth. It was cooked in a burner placed on our table, in front of me, which was quite exciting. The fish is served with its sauce and a large amount of fresh dill - surprising, since it's not a herb I saw at any other point in Vietnam - plus a scattering of peanuts. And, of course, rice. It was absolutely delicious. The fish had been grilled first to give it a lovely caramelised exterior, and then the aromatics of the broth turned it wonderfully moist and flavoursome.

I also had an utterly bizarre plate of food at another restaurant one night. The waitress recommended the 'fish in passion fruit sauce' to me. I was sceptical, but as I love fruit in savoury dishes, and as I didn't want to doubt her taste, I ordered it. What arrived in front of me was a plate of deep-fried fish chunks, smothered in what can only be described as a passion fruit coulis. You know, the kind you get on a cheesecake or a meringue. That is where passion fruit coulis should stay. It is not made to be put on fried fish. The entire thing was totally bizarre, a strange hybrid of main course and dessert. Even I don't like that much fruit in my main courses.

The highlight of our stay in Hanoi was doing a street food tour with Hanoi Cooking Centre. This was a brilliant idea, and I'd really recommend it if you travel to Hanoi, because it demystifies the initially rather intimidating world of street food.

Food in Vietnam is very unlike our English restaurant scene. The best food comes not from restaurants, but out of tiny ramshackle stalls or buildings specialising in a single dish, often perfected over decades by the families that run the stall. I saw women sitting on the middle of the pavement, with a mat on which were placed little bowls of ingredients, shaving green papaya with potato peelers, ready to sell their papaya salads from that very spot. There were vats of noodle broth bubbling away down dark, dingy alleyways, often with a large queue of hungry Vietnamese to match. People sit on tiny stools, the kind we have for children at nursery, in the middle of the street. They don't order, there is no menu, they just sit down and are brought whatever the speciality of that stall is, to wolf down with simple wooden chopsticks from a communal pot.

If you're new to all this, though, it can be a little confusing. Our wonderful guide from the cooking school took us to his favourite street food stops over the course of a morning. We tried some of Hanoi's best street food; as a local, he knew all the best places to take us. First, we breakfasted as the Vietnamese do, with a bowl of steaming pho (pronounced 'fur').

This is often cited as Vietnam's 'national dish', and it's true, there are signs proclaiming 'PHO' nearly everywhere you go. Pho is generally available in two types, though some places specialise in just one. There is pho ga, which is made with chicken, and pho bo, which is made with beef. For both, the making of the broth is an incredibly long process, involving up to 24 hours of simmering bones and aromatics. This flavoursome, clean liquid is ladled into bowls containing a tangle of thick rice noodles, beansprouts, and the meat. It might just be shreds of chicken, or you might also get little meatballs made of chicken and sometimes chicken offal. It might be slices of cooked beef, or beef meatballs, or slices of raw steak that are cooked to rare by the hot broth. The pho is served alongside lime halves and vinegar; our guide told us that the lime is used for pho ga, and the vinegar for pho bo.

I was initially sceptical about the idea of soup for breakfast. Breakfast for me is strictly a sweet meal. Very occasionally I might make myself some eggs on toast, but almost without exception my breakfast consists of fruit with porridge, muesli, or toast. Meat for breakfast is definitely not something that would ever fill me with happiness.

Yet during the frenzy of a month's travelling, a constant medley of euphoric energy and sheer, humid exhaustion, a bowl of cleansing broth in the morning became more than welcome. I actually began to crave it. One of the best bowls of pho I ate was at Dong Hoi station, before catching a train to Hue. I'd woken at 5.45 to get to the station and hadn't eaten. We brought baguettes and jam with us, but rather than eat those, I went to a little stall outside the station and was presented with a beautiful china bowl of broth, topped with the most delicious pink beef slices. It was exactly what my tired body needed, which is perhaps why it remains in my memory as such a highlight.

Pho is more than a bowl of soup; it is the ultimate in comfort food, the ultimate one-bowl meal. Filling, nutritious and soul-saving, pho brightened a couple of very emotional and draining days in Vietnam. Sitting hunched over a wooden bench, squeezing tiny lime halves into the bowl, inhaling the meaty aroma, its steam condensing on your already-sweating face, tangling the slippery noodles around your chopsticks...it's a ritual, one I came to love, and one that I miss the most now I'm home.

The next dish we tried on our tour was one of my favourites; ban cuon. This is a deliciously squidgy pancake made from rice flour batter, which is steamed and then wrapped around a pork and mushroom filling and sprinkled with fried onions, dried shrimp and Vietnamese herbs, served with a dip of fish sauce and lime juice.

One thing that's so addictive about Vietnamese food is the contrast in textures. Here you have deliciously gooey pancake, rather like dim sum dumplings, tender, flavoursome filling, and the crunch of the fried onions and dried shrimp. It's salty and umami-rich, brightened by the sweet-sour-salty dipping sauce. A plate costs 30p, which is just insane. I watched the women at work making the ban cuon: ladling batter onto a sheet of muslin stretched over a bubbling pot, removing it after a few seconds with a palette knife and deftly sliding it onto an oiled work surface, where it was stuffed with its filling before being sliced into pieces and served. It was one of the most delicious, fresh, satisfying things I've ever eaten, and something totally impossible to truly recreate outside Vietnam.

Our guide also showed us this curious water beetle, which he chopped into pieces and put in the dipping sauce. Apparently the juice inside this bug is highly valuable, and it imparted this bizarre floral fragrance to the sauce. I wasn't so keen on it, but initially I thought he wanted us to eat the whole bug, legs and all, so I was a bit relieved (although quite up for trying it, as none of the boys were!).

Another street food dish I loved was ban xao, a rice pancake but this time fried until golden and crispy. It's folded over beansprouts, herbs and shrimp (sometimes other things too, like pork) so it looks rather like a cornish pasty, and at our stall was then cut into pieces (with a pair of rusty scissors - so far removed from the flashy chef's knives of Western cooking) and stuffed inside Vietnamese spring rolls, to be dipped in another sweet-sour dipping sauce. Again, this is all about a contrast of textures, and the crispy fried pancake against the sweet sauce is delicious.

On our street food tour we were also introduced to bia hoi, fresh beer - as a hater of beer this did not excite me, and I was not converted - and Vietnamese coffee, which is fiendishly strong and sweetened with condensed milk. I found it far too sweet, and since even the one sip I did have left me shaking for a good two hours afterwards, it's probably a good thing I didn't develop a taste for it. I did rather love the ritual of putting the simple tin coffee pot over the cup and letting the inky black liquid percolate, though.

We were also taken to a market at the beginning of our tour, where our guide demystified some of the more unusual Vietnamese ingredients. There were huge leafy piles of herbs I've never seen before, and have never seen since. We tasted Vietnamese coriander which, unlike the version we get here, had long, straight leaves. We tried Vietnamese 'fish mint', a minty herb with a strong fish flavour that is apparently an acquired taste, though I liked it. Most Vietnamese food is placed on the table with a tin plate of just-washed fresh herbs, droplets of water still clinging to their leaves. These are placed in spring rolls, scattered over bowls of noodles or immersed in soup at the table, before eating. In England it would seem bizarre to munch on bunches of fresh herbs as part of a meal, but I really enjoyed this tradition in Vietnam. It made the meal seem so much fresher and healthier.

I also got this amazing photo of a chicken for sale. Gruesome and horrible, but quite cool, I think.

Other interesting market highlights were net bags of fertilized duck eggs, i.e. with the embryo inside. I never got to try these (and I'm not too sad about it), but I did find it interesting when our guide explained that the Vietnamese eat them largely for the extra protein from the baby duck bones. Given that meat is expensive in Vietnam, and very few Vietnamese dishes contain much of it, or anything protein-rich, fertilized duck eggs are a valuable source of nutrients. The eggs are kept in a net bag rather than simply in a bowl in case the eggs hatch and the ducks crawl out, which I found a little creepy.

We also saw baskets of fresh turmeric and galangal, bags of live frogs, tubs of huge snails, big plastic bowls with live fish swimming around (the live animal stuff did upset me a bit - one major drawback to life in the far east is the decline in animal welfare standards), meat being hacked up with cleavers while rivulets of blood ran down the ground, and rows of bottled fish sauce. Apparently the best Vietnamese fish sauce is made from black mackerel rather than anchovies, which I found interesting. The key to good quality is if you shake it and see lots of bubbles, and no sediment, as our guide demonstrated for us. I nearly bought a bottle to take home, but thinking of the consequences of it smashing in my suitcase deterred me.

For someone used to buying their produce neatly wrapped in plastic bags in the sterile environment of the Western supermarket, Asian markets are something of a revelation (in both a positive and a negative way). Everything is so much more vibrant, so much more present - you can see, touch, smell and almost taste your ingredients before purchasing them. The fish are still thrashing, the frogs still crawling around - a far cry from the supermarket fish counter, which sometimes houses week-old specimens (though I'd probably prefer that to seeing my fish decapitated in front of me). The fruit is neon-bright, piled high in abundant plenty. The floors are covered in puddles, a mixture of monsoon rain, blood, and fish guts. Motorbikes zoom through aisles barely wider than a human being, up and down steps, so your shopping trip is frequently interrupted by a near-miss moment or the screeching of motorbike horns (a near-constant sound in Vietnam). I couldn't quite believe these mopeds were just screeching around the market without anyone batting an eyelid.

After a relaxing few days wandering the wonderful shops of Hanoi, eating street food, strolling around the lake, getting amazingly cheap (non-dodgy) massages and drinking papaya coconut smoothies, we had a three-day tour of Halong Bay. Nothing special to report here, food-wise - the cruise ship food was lovely, but a lot of it was quite Westernised - but photos of the scenery speak for themselves. We swam in the bath-warm turquoise water, kayaked around the amazing rock formations, and had a fun few hours jumping off the side of our boat into the sea. It was idyllic, in the truest sense of the word.

Our next stop was Phong Nha Ke Bang, a national park in north west Vietnam that has only really just opened to tourists. Containing over 104km of caves and underground rivers, including the largest cave yet discovered in the world, this park houses a treasure trove of geological and ecological interest. If you want all the facts, click the link. If you want to hear what I thought about it, well, it was basically like Jurassic Park.

We arrived at Phong Nha Farmstay, our accommodation for two nights, located in the middle of lush rice paddies near a local village, having just emerged bleary-eyed from the overnight train. We were almost force-fed breakfast (more pineapple pancakes), then rushed onto a tour of the park along with a group of other guests. I initially thought we'd been the lucky ones when we got to ride in the open-topped jeep instead of the minibus; wind blowing through our hair, rock music blaring on the stereo, incredible scenery all around...but then a tropical downpour began. Oops. It took me two days to get dry clothes again.